2021

Salsa!

https://ahippiefarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/PXL_20210912_170806508.LS_.mp4

Fermented Salsa is also a winner in our household. You can vary the flavors anyway you wish and have either a mild one that everyone enjoys or a HOT one that will clear your sinuses.

This is a blend of what the garden has to offer. Tomatoes, Jalapenos and Onions with fermented garlic and a 5.6% brine.

2021

Wrapping up another season…

As another season draws to a close in the Pacific Northwest we are still getting the last of the tomatoes, peppers and cucumbers.

This has been a year for the cucumbers as they seem to be never ending. The real winners this year were SMR pickling and White Wonder both from MIGardener (www.migardener.com).

We have fermented all of them for enough to last at least the whole winter. The winning fermentation method is using the Weck canning jars with the lid and seal along with a weight to keep everything under the brine. This allows the vessel to build up pressure but let some out so it doesn't explode. This makes a firm yet fizzy pickle that is delicious.

See below for the fizzy action....

2021

Pickles, Pickles, Pickles!

Pickles, Pickles, Pickles!

The weather this year has been just what the cucumbers were looking for.

Everyday there is a harvest to be had. This year we are growing

Wisconsin SMR Pickling

Boston Pickling

White Wonder

Straight 9

All varieties from MI Gardener

We are making lots and lots of fermented varieties which will have us getting our probiotics long into the winter.

We have also found some local salt to use in our ferments so our end product is truly all local now.

San Juan Island Sea Salt

2020

Got Beet Tops to Use – Make Kimchi!

This time of year it seems we have lots of vegetation that ends up in the compost bin from the garden harvest.

Some things don't have to end up there, one example is beet tops. This year I decided to try to turn them into something that we could eat instead of just turning them into compost.

This recipe was just beets greens and stems mixed with minced ginger, garlic and salt. Right away it is beautifully colored and on day two we are starting to get some fermenting action. I am exciting to see how it changes over the next few days and will report back on the results.

2020

ONIONS!!

We have a local couple that has decided to help us all support the farmers on the east side of Washington that have a surplus of produce that they cannot get rid of. So we got 50 pounds of red onions for $10! We have turned most of them into fermented onions and pickled onions of several flavors including some with turmeric which are awesome. We will be enjoying these onions for months to come.

2019

Bread!

With the shorter, colder days ahead, here's some Ciabatta bread we made today!

I was intrigued and challenged with the article by William Rubel in the most recent edition of Mother Earth News (December 2019/January 2020). I had always wanted to try making Ciabatta but was always a little intimidated by the end product. After all it looked like something that must be difficult, if not impossible, to achieve.

I was pleasantly surprised, the recipe was easy to follow and the resulting bread was just as delightful as I wanted it to be. Crunchy exterior with a firm yet bubble filled interior, a perfect Ciabatta if I do say so myself.

It provided a warm and comforting addition to a cold November day in the Pacific Northwest.

Thank you Mother Earth News and William Rubel!

#MotherEarthNews #Ciabatta #Bread

2019

Busy Summer Continues

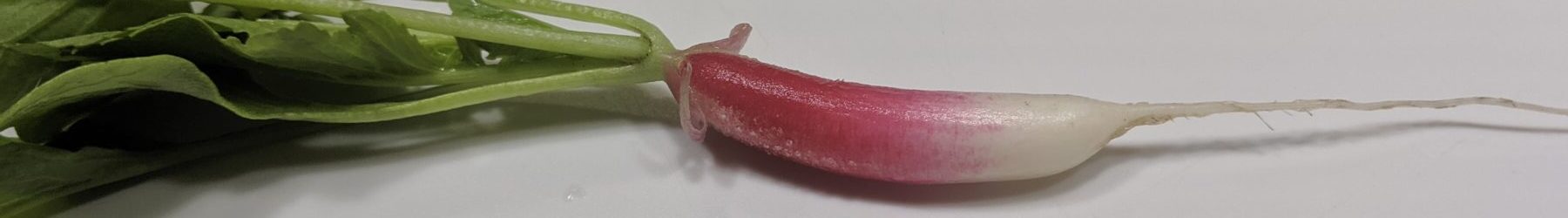

The busy summer continues here in the Pacific Northwest. As other parts of the US are winding down in the garden department we are just now going strong with harvesting.

Things have been crazy here this summer with more varieties of plants to try but more pest pressure than we have had in years past.

The leaf miner battle with the spinach, chard and beets has been a battle of wills for sure. Next year we will use row covers more to try to keep them from taking hold.

Same for the cabbage loopers that tried to destroy the cabbage and brussel sprouts.

But the nasturtiums have done their job and the black aphids have been drawn to them instead of destroying other crops in the garden.

We would definitely advise the potager or kitchen style garden with the mix of flowers and veggies as the companion planting really does benefit all of the crops and gives you plenty of pretty flowers to enjoy as well.

We have found that sharing the bounty of the garden and the products we make from it to be a pleasure and a way to spread the philosophy of fermentation.

We love the fermented products we are able to make from the garden veggies and the possibilities and combinations are endless.

Enjoy the pictures below of the harvest from today and the 3 liters of salsa that I started with just today's' tomatoes. In a few days we will have more salsa to enjoy and share!

2019

Weck Jars

After being raised with the traditional american Mason jars I have discovered that the German made Weck jars are superior in many ways. They have reusable glass lids and rubber gaskets which eliminates waste on single use products. They are more expensive on the front end but some far have lasted a lot longer and are made of thicker glass that is more durable. Several different shapes and sizes to choose from. They are also great for fermentation. Check out some of their offerings below.

2019

Pickles

A new batch of pickles is brewing. These are the best pickles we have ever made and this method has turned out great each and every time.

5.6 % salt brine, cucumbers, fermented garlic, dill, tea bag (to keep them crisp) plus time = awesome pickles.

Taste every few days and refrigerate once they taste good to you.

2019

Fermentation

We have dabbled with fermentation for several years, starting with a referral to the book by Sandor Katz – Wild Fermentation. We continue to learn more with each batch of pickles, yogurt, sauerkraut, kimchi, etc. It is an exciting world of flavors, textures and colors that fail to disappoint.

I would be lying if I said we never had a failure that we ending up composting instead of consuming. But it is a journey through the different stages of fermentation that bring different levels of fantastic nourishing flavor.

I encourage everyone to give it a try. At least pick up a book and read about the ways that these wonderful experiments can improve your gut health while providing a tasty addition to each and every meal.

We will cover more about this interesting topic including different methods and equipment (you don’t need a lot of expensive equipment to make this work). The photo below shows salsa in the works in a Weck jar. The unique seal allows the gases to escape while the food is fermenting.

Check out the following:

https://www.wildfermentation.com/

http://weckjars.com/

#fermentation

#sandorkatz

#weckjars