A Comprehensive Guide to Creating a Sourdough Starter from Scratch: The Sandor Katz Inspired Method

Sourdough starter, also known as a “mother” or “levain,” is a living culture of wild yeasts and bacteria that naturally leaven and flavor bread. Creating one from scratch is a rewarding process that connects you to ancient baking traditions. Sandor Katz’s philosophy embraces the simplicity and natural magic of fermentation.

The Core Principle: You are creating a hospitable environment for wild yeasts (which are all around us – in the air, on surfaces, and especially on the bran of grains) and beneficial bacteria to thrive. These microorganisms will consume the carbohydrates in flour, producing carbon dioxide (which makes bread rise) and organic acids (which give sourdough its characteristic tangy flavor).

What You’ll Need:

- A Clean Jar or Non-Reactive Container: Glass is ideal as you can see the activity. A quart-sized (approx. 1 liter) jar is a good starting point. Avoid metal containers, especially aluminum or copper, as they can react with the acidic starter. Stainless steel is generally considered safe if that’s all you have.

- Flour:

- Best Choices for Starting: Whole grain flours like whole wheat or rye are often recommended for starting a starter. They contain more microorganisms and nutrients on the bran and germ, which can help kickstart activity. Organic flours are also a good choice as they are less likely to have been treated with fungicides that could inhibit microbial growth.

- Other Options: Unbleached all-purpose flour can also work, though it might take a little longer to show activity.

- Avoid: Bleached flour, as the bleaching process can damage the microorganisms needed.

- Water:

- Best Choices: Filtered, spring, or well water are ideal.

- Tap Water: If using tap water, it’s best to let it sit out uncovered for at least a few hours, or ideally overnight, to allow any chlorine to dissipate, as chlorine can inhibit microbial growth. Alternatively, you can boil it for a few minutes and let it cool completely.

- Optional – For an Initial Boost (Katz’s Fruit Suggestion):

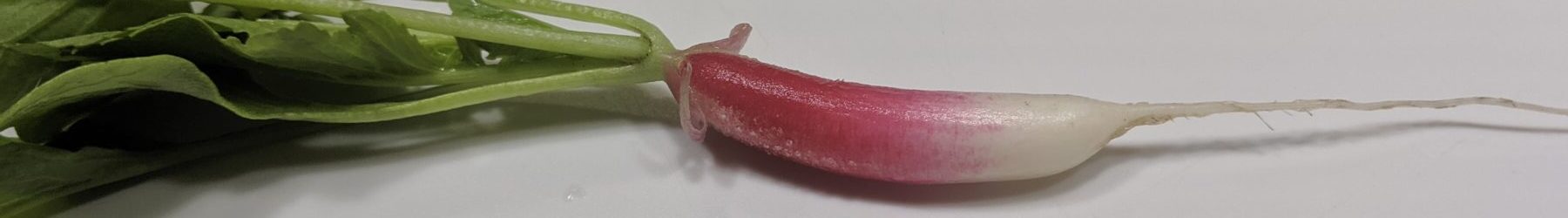

- A few pieces of unwashed, thin-skinned organic fruit like grapes, plums, berries, or even a piece of apple peel. The waxy bloom on the skin of such fruits is rich in wild yeasts.

- A Porous Cover: Cheesecloth, a clean kitchen towel, a coffee filter, or a loosely fitting lid. This allows air to circulate and wild yeasts to enter while keeping out dust and insects.

- A Non-Reactive Utensil for Stirring: Wood, silicone, or stainless steel spoon/spatula.

Detailed Step-by-Step Guide:

Phase 1: Initiating the Culture (Days 1-7+ )

This phase is about inviting and cultivating the initial microbial community. Patience is key here; development times can vary greatly depending on your flour, water, ambient temperature, and the specific microorganisms present in your environment.

- Day 1: The Initial Mix

- Prepare your Jar: Ensure your jar is clean. You don’t need to sterilize it, but it should be well-washed.

- Combine Flour and Water: In your jar, combine approximately 1/2 cup (around 60g) of your chosen flour with 1/4 cup (around 60g) of non-chlorinated water. Aim for a thick, lump-free batter consistency, like pancake batter or thick paint. Adjust with a little more flour or water if needed. Stir vigorously to incorporate air.

- (Optional) Add Fruit: If using, gently add your unwashed fruit pieces into the mixture. Don’t chop them finely; a few whole grapes or a slice of plum is fine.

- Cover: Cover the jar with your porous material, securing it with a rubber band or the jar’s screw band (if using a canning jar, don’t use the sealing lid).

- Location: Place the jar in a consistently warm spot, ideally between 70-80°F (21-27°C). A kitchen counter, on top of the refrigerator, or in an oven with just the light on (be very careful it doesn’t get too hot) can work. Avoid direct sunlight, which can overheat the starter. Good air circulation is also beneficial.

- Day 2: Observation and Stirring

- Observe: You might not see much activity yet, or you might see a few tiny bubbles. It might smell mostly like wet flour.

- Stir: Uncover and stir the mixture vigorously at least once, preferably twice a day. This reincorporates ingredients, introduces oxygen (which some initial desirable microorganisms appreciate), and helps distribute developing cultures. If you added fruit, just stir gently around it.

- Days 3-7 (and potentially longer): Waiting for Signs of Life

- Continue Stirring: Stir 1-2 times daily.

- Observe Closely:

- Bubbles: This is the primary sign you’re looking for. They might be tiny at first, then become more noticeable. This indicates yeast activity (carbon dioxide production).

- Aroma: The smell will change. Initially, it might smell a bit “off” or overly pungent (sometimes like old cheese or smelly socks). This is often due to different types of bacteria competing. Don’t be discouraged! As the desirable lactic acid bacteria (LAB) take hold, the aroma should evolve into something more pleasantly sour, yeasty, fruity, or even vinegary. A “hooch” (a layer of liquid on top) might form, which can smell alcoholic or like nail polish remover. This is normal; just stir it back in.

- Expansion (Rise and Fall): Eventually, you may see the starter increase in volume after stirring/feeding, and then fall back down.

- First “Feeding” (once definite activity is observed):

- Once you see consistent small bubbles and a noticeably changed, perhaps pleasantly sour or yeasty aroma (this might be anywhere from day 3 to day 7, or even longer in cooler environments), it’s time for the first “refreshment” or feeding.

- If you added fruit, strain it out and discard it now.

- Discard about half of your initial mixture. This might seem wasteful, but it’s important to keep the acidity in check and ensure the microorganisms have enough fresh food.

- Add fresh flour and water, similar to your initial amounts: roughly 1/4 cup (30g) flour and 2 tablespoons (30g) water. Mix well. The consistency should again be like a thick batter.

- The idea of “a few more days until you have a thick, bubbly batter” from the original instructions fits here. This “feeding” step is what refines the culture.

Phase 2: Establishing and Strengthening the Starter (Daily Feedings)

Once you’ve seen initial activity and performed the first feeding (after removing fruit), you move into a routine of regular feedings to strengthen the yeast and bacteria populations.

- Daily Routine (or Twice Daily if very active and warm):

- Observe: Look for bubbles, expansion, and note the aroma. A healthy, active starter will typically rise predictably after feeding and have a pleasant, tangy smell.

- Discard (or Use/Save): Before each feeding, you’ll need to discard a portion of the starter. A common practice is to keep about 1/4 to 1/2 cup of starter (e.g., 50-60g) and discard the rest. (The discard can be saved in the fridge and used in recipes like pancakes, waffles, or crackers).

- Feed: To the remaining starter, add fresh flour and water. A common ratio is 1:1:1 by weight (starter:flour:water). For example, if you kept 50g of starter, you would add 50g of flour and 50g of water. If you’re measuring by volume, this could be something like keeping 1/4 cup of starter and adding 1/4 cup of flour and slightly less than 1/4 cup of water (around 2-3 tablespoons) to maintain a thick batter consistency.

- Mix: Stir vigorously.

- Cover and Wait: Place it back in its warm spot.

- What to Expect:

- Over several days to a week (or more) of consistent feedings, your starter should become more predictable. It should ideally double (or more) in volume within 4-8 hours after feeding (this time can vary based on temperature).

- The aroma should be distinctly sour and yeasty, but pleasant.

- The texture will be bubbly and airy at its peak.

- When is it Ready?

Your starter is generally considered “ready to use” for baking when:

- It reliably doubles or triples in volume within a few hours (e.g., 4-8 hours) after feeding at room temperature (around 70-75°F or 21-24°C).

- It is full of bubbles, both large and small.

- It has a pleasant, tangy, yeasty aroma (not an off-putting or overly “bad” smell).

- The Float Test (Optional but common): Drop a small spoonful of active starter into a glass of water. If it floats, it’s generally considered ready and airy enough to leaven bread. However, some perfectly good starters may not float, so don’t rely on this exclusively.

This whole process, from Day 1 to a reliably active starter, can take anywhere from 7 to 14 days, sometimes longer, sometimes a bit shorter.

Phase 3: Maintaining Your Mature Starter

Once your starter is robust and predictable, you have a few options for maintaining it:

- Room Temperature Maintenance (If you bake frequently, e.g., several times a week):

- Keep the starter on your counter.

- Feed it once or twice a day, following the discard and feed routine. Twice-a-day feedings (every 12 hours) will keep it very vigorous. Once-a-day (every 24 hours) is also common.

- Refrigerator Maintenance (If you bake less frequently, e.g., once a week or less):

- Feed your starter. Let it sit at room temperature for a few hours (2-4 hours) to get active.

- Then, cover it tightly and place it in the refrigerator.

- The cold temperature will slow down fermentation significantly.

- You’ll need to take it out and feed it at least once a week. To do this:

- Remove it from the fridge.

- If there’s hooch, you can stir it in or pour it off (stirring it in will make it more sour).

- Discard a portion and feed it as usual.

- Let it sit at room temperature to become active (it might take a couple of feeding cycles to become fully vigorous again if it’s been in the fridge for a while). If you plan to bake, you might do 2-3 feedings at room temperature over 12-24 hours before using it.

- Once active, you can use it for baking or return it to the fridge after a few hours at room temperature post-feeding.

Important Considerations & Tips for Success (Sandor Katz Style and General Wisdom):

- Trust Your Senses: Your nose is one of your best tools. The aroma of the starter will tell you a lot about its health and activity. It should evolve from just floury to potentially funky, and finally to pleasantly sour and yeasty.

- Temperature is Key: Yeast and bacteria activity is highly temperature-dependent. Warmer temperatures (within the ideal range) speed up fermentation; cooler temperatures slow it down. If your kitchen is cold, your starter will develop more slowly.

- Consistency of Flour and Water: While Sandor Katz emphasizes flexibility, using the same type of flour and water consistently during the initial development can help establish a stable culture more quickly. Once mature, starters are often more resilient to changes.

- “Hooch”: The liquid layer that can form on top is called hooch. It’s a byproduct of fermentation and indicates your starter is hungry. It’s usually alcoholic and can be stirred back in (for a more sour flavor) or poured off before feeding. Frequent hooch formation means you might need to feed your starter more often or with a higher ratio of fresh flour and water.

- Mold:

- White, “fuzzy” mold: If you see small amounts of white mold that isn’t deeply embedded, you can try to carefully scrape it off, along with a good margin of the starter underneath, and transfer a clean portion from the very bottom of the jar to a new clean jar and feed it. Monitor it closely.

- Colored Mold (Pink, Orange, Green, Black): This is a bad sign. If you see pink, orange, or fuzzy black/green mold, it’s best to discard the entire starter and begin again. These can indicate harmful bacteria. This is why ensuring good airflow and a clean environment is important.

- Activity Lulls: It’s common for starters to show a burst of activity in the first few days (sometimes due to bacteria other than the desired sourdough yeasts and LAB), and then appear to go dormant or “die” for a few days (often around days 3-5). This is often a phase where the pH is dropping, and the desired yeasts and lactic acid bacteria are working to become the dominant cultures. Don’t give up! Keep stirring and then resume feeding once activity (even slight) reappears or after a couple of days of no activity.

- Don’t Be Afraid to Experiment (Once Established): Once your starter is mature and robust, you can experiment with feeding it different types of flours to influence the flavor of your bread. Rye makes it more sour; wheat can be milder.

- No Need for Commercial Yeast: The whole point is to cultivate wild yeasts. Adding commercial yeast will outcompete the wild strains you are trying to nurture.

- Patience is a Virtue: This is a natural process. Some starters spring to life quickly; others take their time. Be patient, observe, and adjust your care as needed. The environment in your kitchen, the flour you use, and even the season can affect the process.

By following these steps, inspired by Sandor Katz’s approach of working with natural cultures, you’ll be well on your way to creating a vibrant, active sourdough starter ready for baking delicious, naturally leavened bread. Enjoy the journey!